June 30, 2018

Previously we have discussed some of the more practical (if not prosaic) uses of aluminum in our everyday lives, from car manufacturing to building construction to solar panels, and even in robotics. One delightful area we have not touched on yet is the use of aluminum for purely aesthetic purposes: in the making of art.

It’s hard to imagine an elemental metal more suited than aluminum for creating beautiful objects. For one thing, there’s plenty of it: aluminum is the third most abundant element on Earth and the most abundant metal, making up some 8% of the planet’s crust. This durable metal is strong yet light, has a pleasing silvery-white appearance, can be polished to a highly reflective sheen, and is resistant to oxidation and corrosion. Though sometimes a “finicky” metal to work with (due to its relatively low melting point and high heat-conductiveness), it is also a versatile one: it is both ductile and malleable and can easily be molded, extruded, bent, stamped, cut, riveted, and welded. It can even be successfully painted and glued, since finishes and adhesives retain 100% of their strength when bonded to aluminum, thanks to its unique chemical properties.

Given all this, the world should be fairly bursting with astonishing artworks made from aluminum. And yet such treasures are few and far between compared to artworks made with other materials.

When one considers the various types of metals and alloys that have been commonly employed in the plastic arts since the dawn of human history, some of the first and most obvious ones that may spring to mind include gold, silver, bronze, brass, copper, iron, and lead. Aluminum is actually a very recent addition to this list of metals traditionally favored by sculptors and artisans. And there’s a very good reason for that.

It wasn’t until 1827 that German chemist Friedrich Wöhler perfected a method of producing a pure form of the metal; even so, the process of extracting aluminum from bauxite ore proved so costly and difficult that for a time this “rare” metal was more valuable than gold! In the 1880s, however, scientists devised a practical method (by electrolysis) of isolating large quantities of aluminum from bauxite. After that, the price of aluminum plummeted. As Sam Kean writes in his book, The Disappearing Spoon: And Other True Tales of Madness, Love, and the History of the World from the Periodic Table of the Elements:

Aluminium’s sixty-year reign as the world’s most precious substance was glorious, but soon an American chemist ruined everything.

By the early 20th century, this abundant, cheap, light, flexible, and non-toxic metal flooded the market and became widely used by the construction and transportation industries and in everyday items such as cooking and tableware, food containers, jewelry, eyeglass frames, furniture, and other commercial products.

Sculptors, craftsmen, and other artists too were quick to recognize the benefits of creating with aluminum. Here are just a few of their most notable artistic accomplishments.

The Nanjing Belt

As mentioned above, until less than two centuries ago there was no known method of reliably producing pure aluminum in any significant quantity. And yet, here is this tantalizing historical tidbit. In 1952 Chinese archaeologists excavated the tomb of Zhou Chu, a general and nobleman who lived in the 3rd century A.D. Among the artifacts discovered there was a set of curious metal ornaments, apparently a decorative belt of some sort. Subsequent chemical analysis revealed these artifacts to be composed of 85% pure aluminum—centuries before the metal was even known to exist! Whether academic prank or metallurgic miracle, this discovery remains to this day a conundrum to archaeologists and chemists alike.

Pieces from the Nanjing Belt

The Washington Monument Capstone…

…ironically enough, is not made of stone at all. The tallest structure (by law!) in the District of Columbia, this famed obelisk was completed in 1884 and is capped at its apex with a small aluminum pyramid with inscriptions on all four sides. Nine inches tall and weighing in at 100 ounces, this pyramid was cast by architect William Frishmuth of Philadelphia, whose aluminum foundry was the only one in the U.S. until the late 1880s. It was the largest single piece of solid aluminum at the time, when the metal still commanded a price comparable to silver. Indeed, it proved such a novelty that it was displayed at Tiffany’s jewelry store in New York for public viewing before being placed atop the monument.

Aluminum Apex of the Washington Monument [source]

Anteros

Statue of Anteros in Piccadilly Circus [source]

The Greek god of requited love (and brother of Eros), Anteros is the subject of the Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain in Piccadilly Circus, London, which was erected in 1893 to commemorate the selfless philanthropic love of the Earl of Shaftesbury for the poor. Cast by English sculptor and metallurgist Alfred Gilbert, this was the world’s first statue made completely of aluminum. It has been called “London’s most famous work of sculpture.”

Violin

Aluminum Violin [source]

If one subscribes to the idea that every musical instrument ever made is a work of art, then this certainly qualifies.

First produced in 1932 by the Aluminum Musical Instrument Company, Inc. in Ann Arbor, Michigan, this violin was fitted with spruce soundboards, but the body was pressed from a single piece of Alcoa aluminum and painted to resemble natural wood grain.

Religious Art

Holy Water Font [source]

This all-aluminum church holy water font, on exhibit at the Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum in Germany, dates from around World War I (1914–1918).

Don Quixote

Lauded for combining both skillful realism and emotional depth in her equestrian and other animal statuary, American artist Anna Hyatt Huntington founded Brookgreen Gardens near Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, a 9,170-acre sculpture garden and wildlife preserve. In Don Quixote (1947) she depicts in cast aluminum the emaciated visionary carrying a broken lance and riding a weary Rosinante, with head down and tail between his legs. Trailing behind is Don Quixote’s long-suffering but faithful squire, Sancho Panza, also in aluminum (by Carl Paul Jennewein, 1971).

Don Quixote [source]

Abstract Art

Aluminum’s coming of age as a suitable and readily available sculpting material coincided with the rise of the modern art movement, and so one can find numerous examples of abstract sculpture made with aluminum all around the world. The striking Hari IV (1982) by renowned American artist Bill Barrett is made from fabricated aluminum, stands some 30′ tall, and is located on the campus of New Dorp High School in Staten Island, New York.

Public Art

Suspended on wires from the roof of St. Pancras railway station in central London, Thought of Train of Thought by sculptor and Royal Academician Ron Arad comprises an 18-metre twisted blade of aluminum, rotating slowly above the crowd of passengers to create a hypnotic optical illusion.

Art in Design

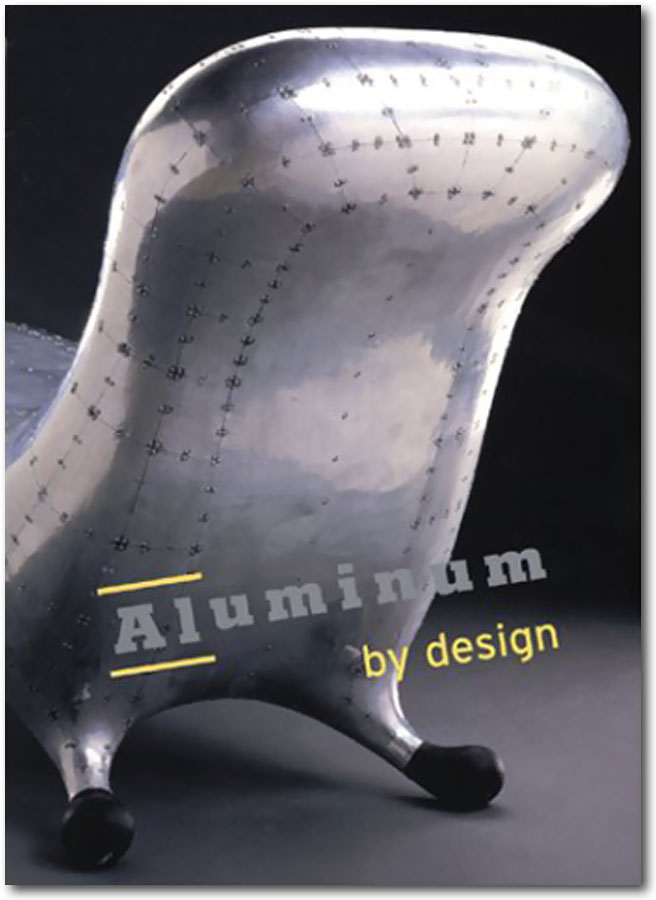

Also by Ron Arad, the commercially popular Tom Vac chair, constructed from vacuum-formed aluminum, actually began as a component of a sculpture installation, titled Totem, comprising 100 such chairs stacked on top of each other in a square in Milan during the 1997 Design Week.

Found Art

When it comes to transforming trash into treasure, you’d be hard-pressed to find a more plentiful raw material than discarded aluminum soda and beer cans. And sure enough, there is an artist who specializes in doing just that. Noah Deledda uses just his thumb and fingers to meticulously crease and dent the surface of this commonplace, disposable object, creating stunning three-dimensional sculptures adorned with flawless, geometric patterns—worthy to be displayed in any art museum!

As you can imagine, in this article we have just scratched the surface of a fascinating topic. If you’d like to delve deeper, check out the book Aluminum by Design (2000) by Sarah Nichols et al., which accompanied a major traveling exhibition from Carnegie Museum of Art showcasing works of art and design in aluminum by some truly visionary designers and architects, from chairs and tables to jewelry and entire buildings.

And while you’re at it, come see some of our own beautiful design solutions in aluminum at our website.

Chris Hill is the President and CEO of Framing Technology, Inc. Connect with him on Google+ and Twitter.